Over the past three years, UPD has helped two state education agencies (SEAs) develop and implement their Local Education Agency’s (LEA) performance management processes to support effective implementation of their Race to the Top initiatives. In a nutshell, these processes involved the facilitation of ongoing, structured meetings attended by LEA leadership team members during which participants actively engaged with teams from other districts around challenging problems of practice and promising strategies for addressing these challenges.

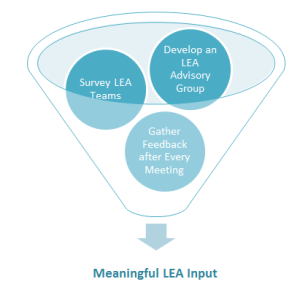

Rhode Island and Illinois, the SEAs that implemented these processes with support from UPD, both deliberately incorporated LEA input into their planning and continuous improvement efforts. Through the strategic use of online surveys, appointing an LEA advisory group, and diligently gathering and analyzing feedback after every meeting, both states ensured that not only were the sessions helpful to LEAs but that participants felt ownership over the work and saw the SEA as better partners than in past implementation efforts.

Having an LEA focus truly means that the meeting discussions are LEA-centric and focused on what the LEAs need, rather than on what the SEA thinks should be discussed. When this happens, the conversations provide LEA and SEA participants with rich and often unexpected insights into implementation successes and challenges. Session facilitators can promote an LEA focus by asking open-ended questions about lessons learned and challenges facing the districts in their groups, and reinforcing the practice of LEA teams deliberately asking and answering questions of teams from different LEAs, rather than turning to the SEA representatives in the room for answers.

Building positive relationships with LEA stakeholders does not happen overnight. People often have to move past previous experiences where the SEA and LEAs were not aligned regarding expectations for implementation which led to low levels of trust between LEAs and the SEA. Transparent communication by SEAs is critical in reinforcing a positive partnership with LEAs.

SEAs can build trust by continuously providing timely turnaround on the sharing of lessons learned and resources, and by clearly and regularly articulating, “Here is what you told us, and this is what we did because of your input.” Even when there is not an obvious or immediate solution, it is an opportunity to practice transparent and deliberate communication and further build trust with LEAs.

En fin de compte (as my high school French teacher was fond of saying and which translates to “In the final analysis…” in English), SEAs that:

- deliberately engage LEAs in process and content design,

- respond clearly and consistently to LEA suggestions and questions, and

- provide meaningful opportunities for LEA teams to share their challenges and strategies,

will see increased LEA ownership of implementation success, improved relationships with LEAs and a greater understanding of “on-the-ground” implementation challenges and effective strategies.

More information on this issue is forthcoming in a Brief authored by UPD for the US Department of Education’s Reform Support Network. Details and a link coming soon!

Written by Elaine Farber Budish, a Senior Consultant at UPD Consulting (elaine@updconsulting.com), September 2014

Photo by

Photo by